Cris Contini Contemporary

Exhibitions & Art Fairs

2022 At my window... A XXIst century vision of landscape art | LKFF Art Projects, Beersel, Belgium

2019 ArtVerona | Cris Contini Contemporary, Verona, Italy

2019 Opening Show | Contemporary & Co., Cortina D’Ampezzo, Italy

2019 ArtePadova | Cris Contini Contemporary, Padova, Italy

2019 Opening Show | Cris Contini Contemporary, Mayfair, London, UK

2018 Solo Exhibition | XXS Aperto al Contemporaneo, Palermo, Italy

2018 Solo Exhibition | Costantini Art Gallery, Milan, Italy

2017 Opening Show | Pontone Gallery, Chelsea, London, UK

2017 Winter Show, Part II | Albemarle Gallery, Mayfair, London, UK

2016 Winter Show | Albemarle Gallery, Mayfair, London, UK

2016 Solo Exhibition | Albemarle Gallery, Mayfair, London, UK

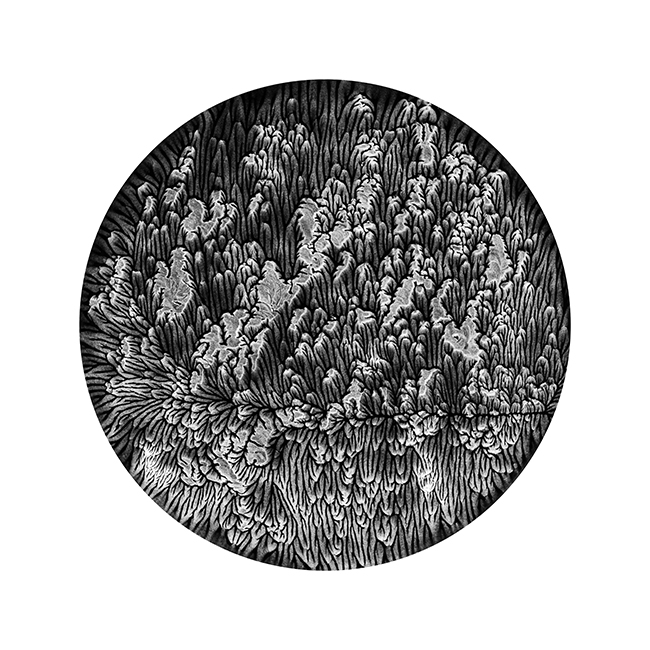

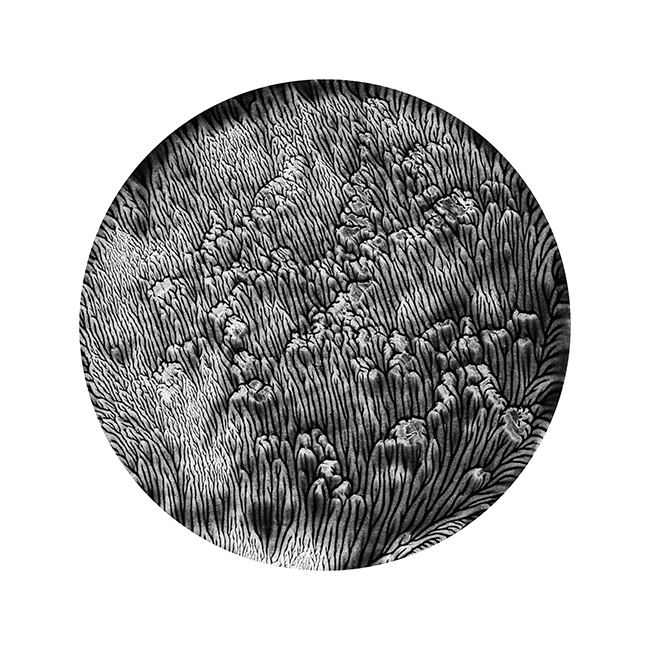

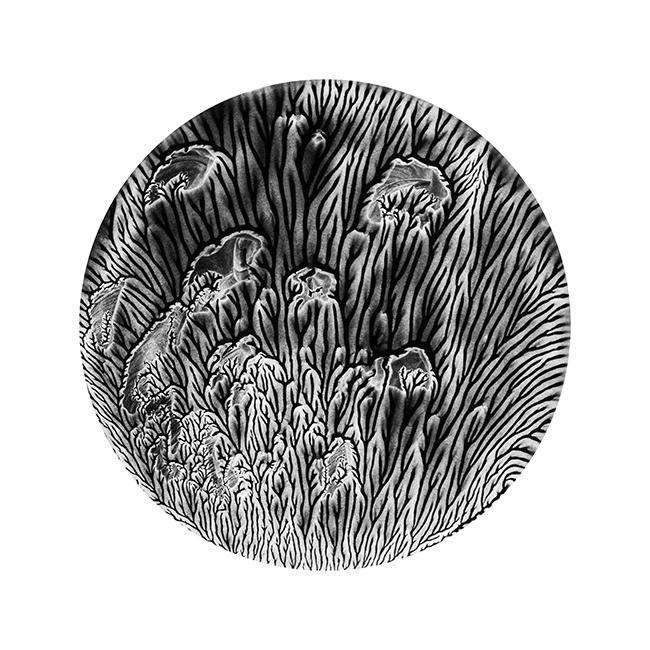

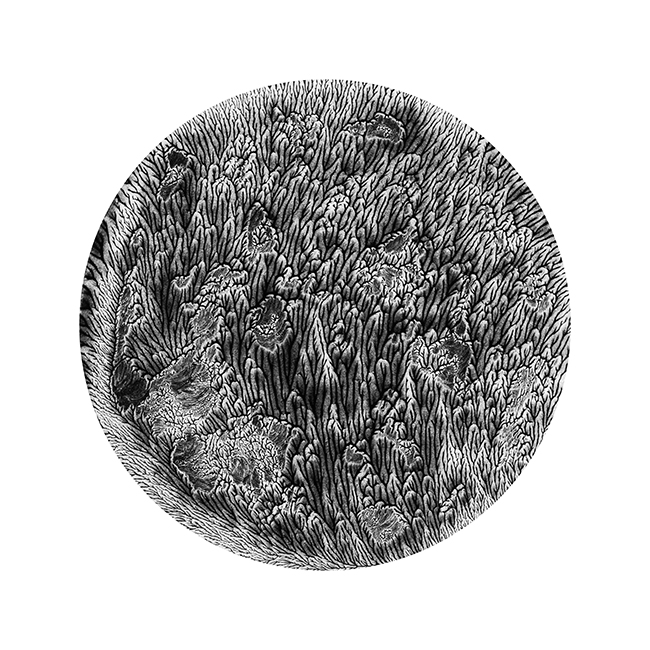

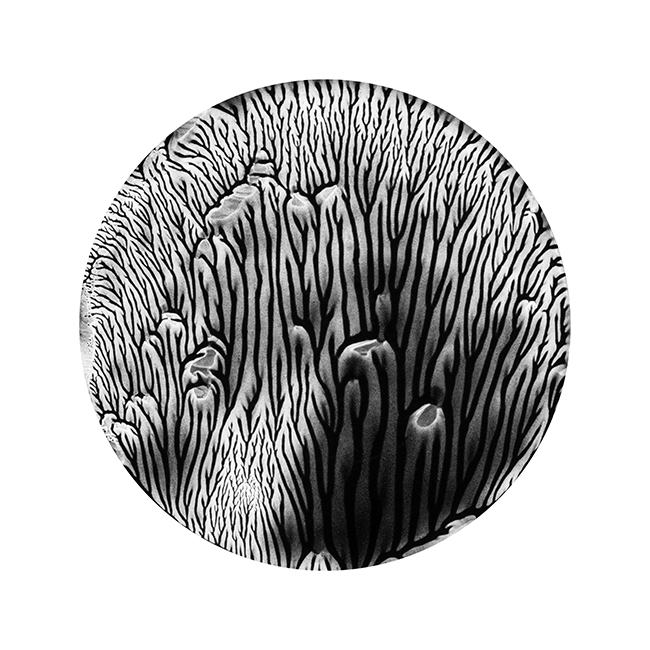

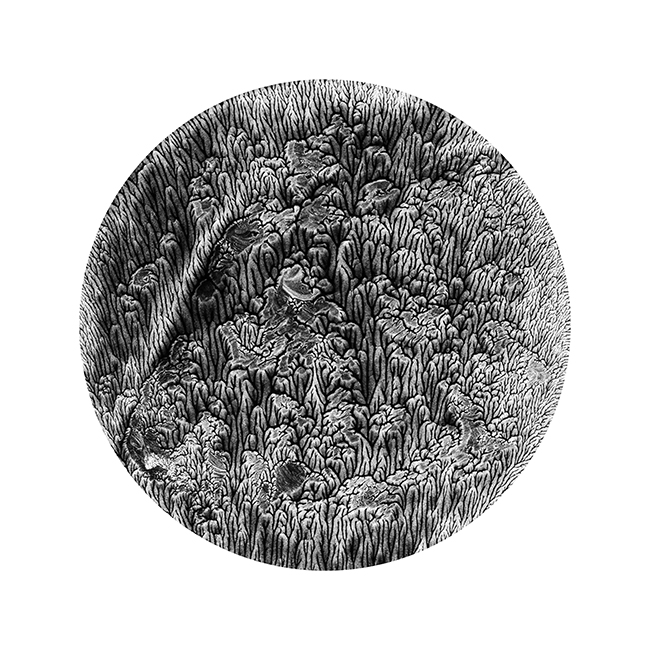

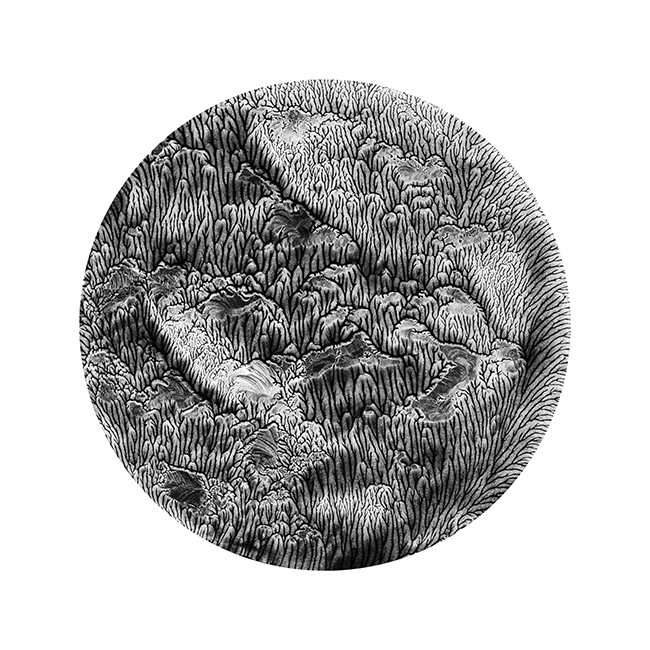

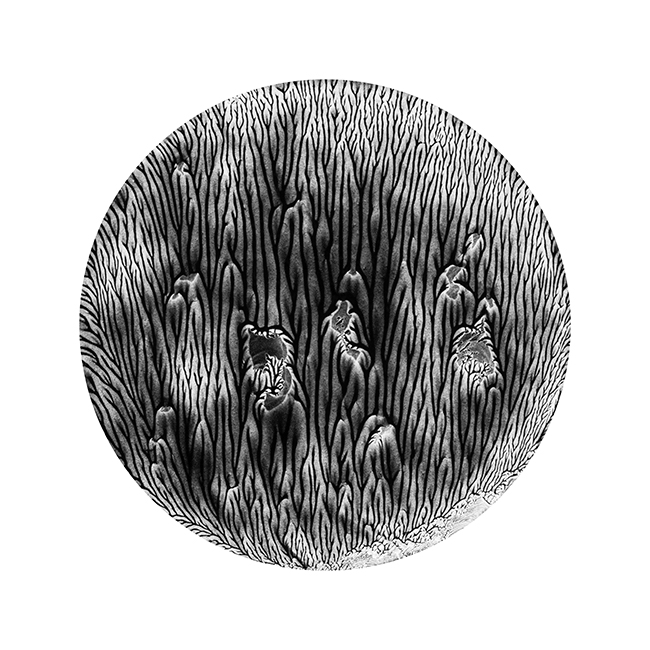

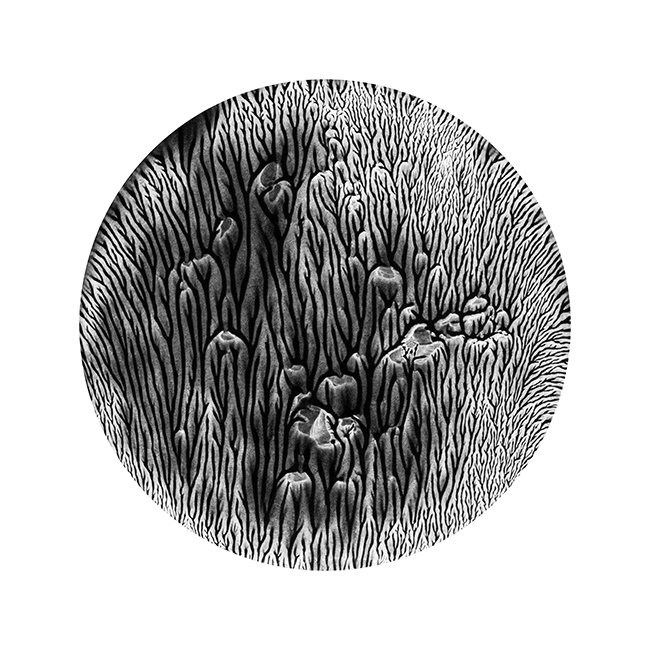

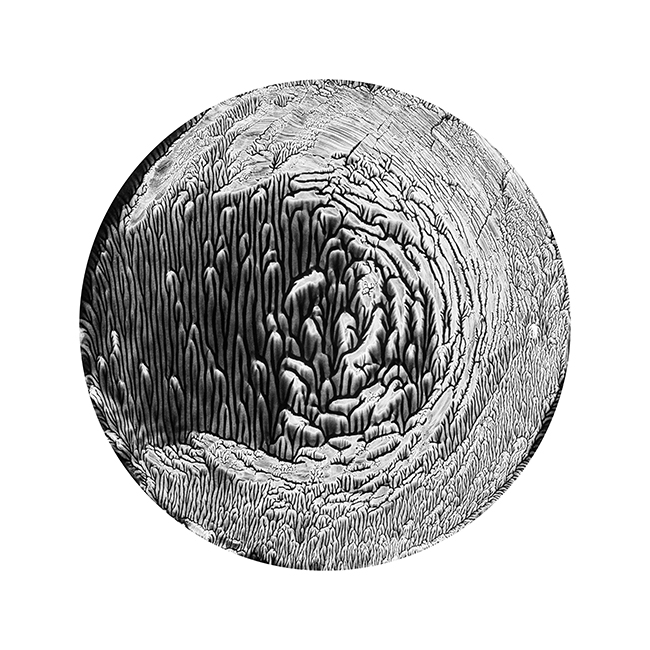

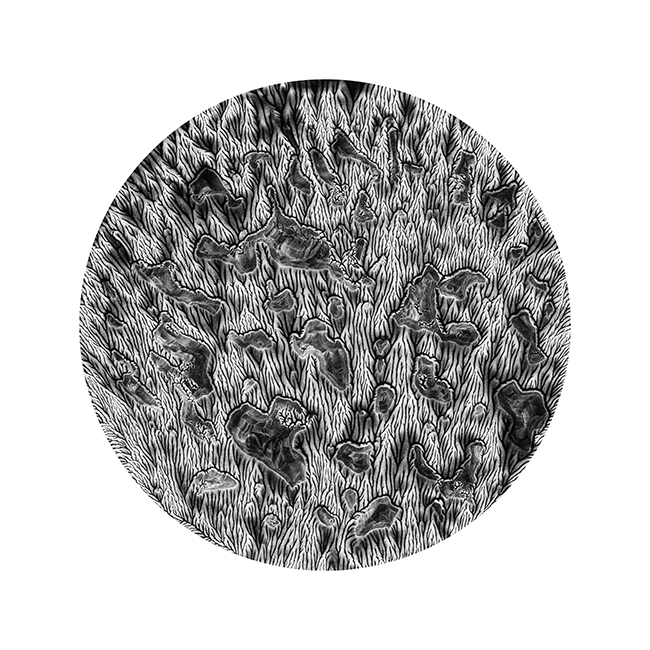

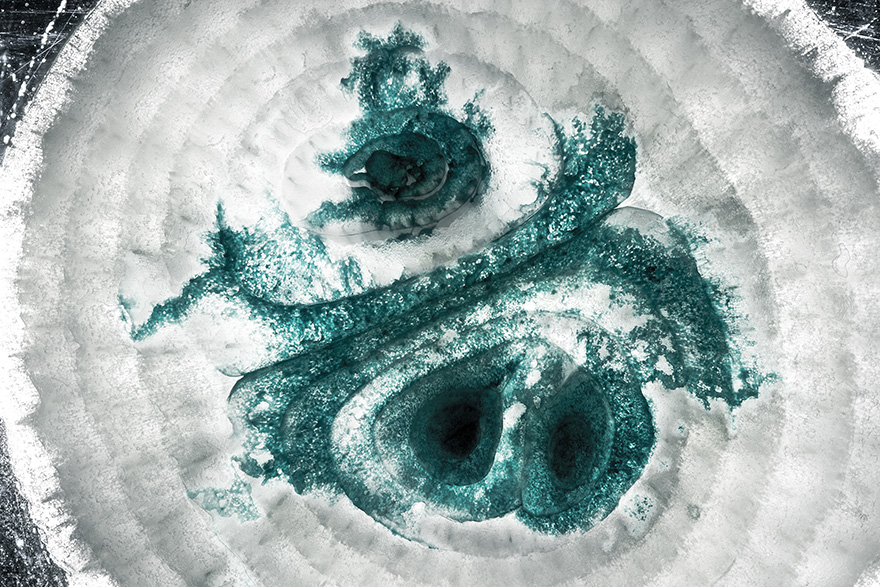

Obsidian Fields

Archival Pigment Print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag under Museum Glass (framed) | 2022

Editions of 5 + 1AP: 67 x 67 cm (26 x 26 in)

Editions of 5 + 1AP: 86 x 86 cm (34 x 34 in)

Editions of 5 + 1AP: 67 x 67 cm (26 x 26 in)

Editions of 5 + 1AP: 86 x 86 cm (34 x 34 in)

|

|

|

|

|||

106 |

115 |

117 |

121 |

|||

|

|

|

|

|||

130 |

132 |

145 |

148 |

|||

|

|

|

|

|||

152 |

153 |

155 |

162 |

|||

|

|

|

|

|||

165 |

168 |

177 |

183 |

|||

|

|

|

|

|||

188 |

189 |

190 |

198 |

|||

Editions of 5 + 1AP: 86 x 86 cm (34 x 34 in)

Editions of 5 + 1AP: 111 x 111 cm (44 x 44 in)

Editions of 5 + 1AP: 111 x 111 cm (44 x 44 in)

|

|

|

|

|||

223 |

242 |

247 |

256 |

|||

|

|

|||||

282 |

291 |

|||||

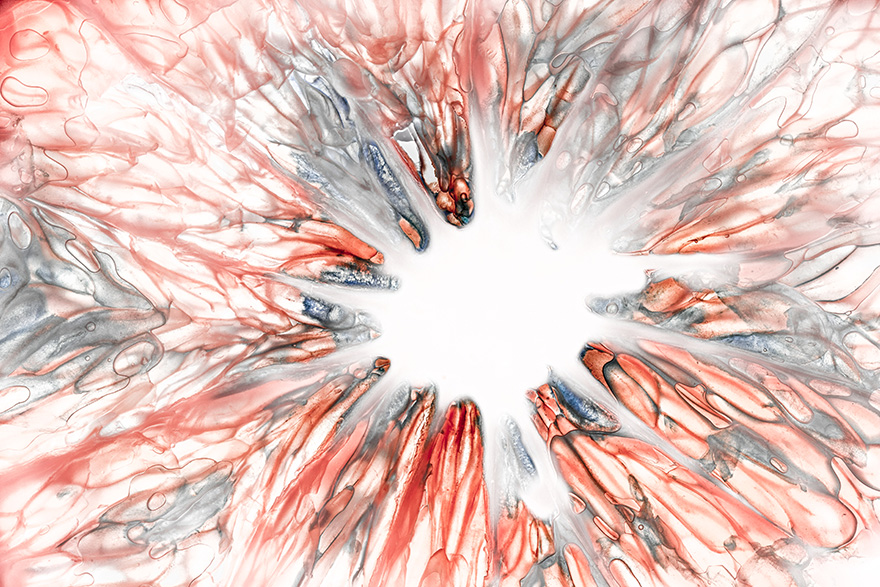

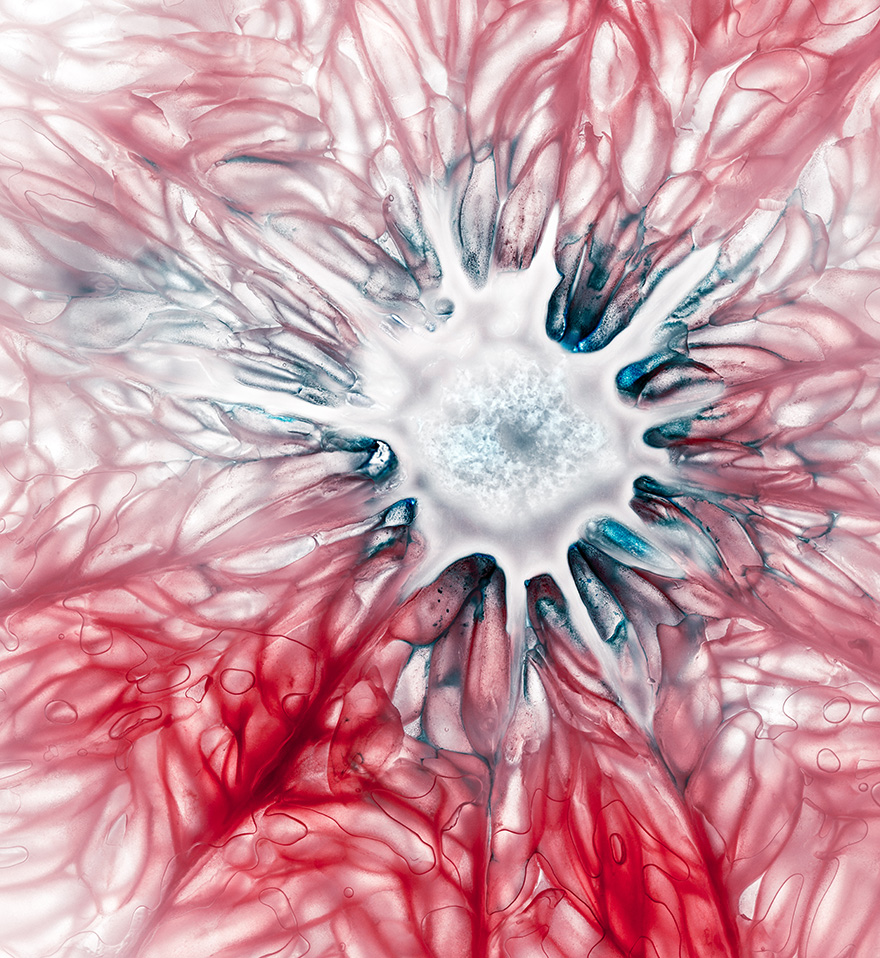

Photography, like all art (and science), is primarily research. Like many technical innovations that arose in the 19th century, it is a continuous becoming, an uninterrupted flow of changes born of time and new discoveries in the scientific field.

Although photography is considered one of the forms of artistic communication, it is true that the creation process, after the idea, is a procedure that captures the truth of the real world as an image, whether on film or on a digital sensor. However, as photographic devices and techniques have evolved over time, so has our idea of reality, which has moved beyond that of a familiar cityscape or landscape.

The photographer, driven by a deep spirit of research, is no longer satisfied with man-made structures or what nature provides: he uses and manipulates what exists to capture new perspectives, novel variations on which to focus his lens, in an attempt to bring forth a different world. And it is exactly at this moment that this project is born, from Vins Blake, a photographer at the intersection of science and art, determined to tell a new story — that of the Obsidian Fields.

According to Ansel Adams, "You don't take a photograph, you make it.”, and this is what makes the difference in photography; the creative act is the moment when Blake combines the artist with his being a scientist, letting two worlds interact with each other and become reality, or, in this case, photography. The Obsidian Fields were still and unexplored realm, an idea set in motion at the interface between black pigment and glass, waiting to bloom according to the direction the mark left would take.

Chiaroscuro, shapes that occupy their space with soft but purposeful movements; an undefined microcosm that moves under the input of the photographer, on a surface that is circumscribed yet free at the same time. Reducing the lines to something known, familiar, takes away from the value of the images, which instead gain strength if we just follow that gentle movement of the color, expertly manipulated by the photographer, that becomes the generating principle of the entire series.

Static images that seem to move in space, traces that meet the gaze of the interlocutor who becomes a privileged observer, now able to look inside the narration itself, as if the circle were a window to lean out of, not the maximum limit within which to see. Photography as the beginning of the story, at the artist's will, while the rest of the discovery is the unique prerogative of the beholder.

Only by "reading" the entire Obsidian Fields series as if it were the pages of a book, will its meaning, value, and message be understood. Each shot a fragment of the story, each nuance a sentence, each trace a delicate thread to follow, in order to reach the creation’s inherent significance. Looking at the shots of Obsidian Fields means seeing through the eyes of the artist. No longer an investigative tool, they are organs capable of capturing a reality now made objective by the relationship between artistic intuition and that abstract space that has become the natural theater of the photographs.

The use of black acrylic — combined with the artistic idea — leaves the images suspended in their perspectival space, as in a continuous game in which Blake challenges himself by entrusting the observer with the nuances, the essence, without distorting the original message. Eminently fitting is a statement from Heinrich Wölfflin, art historian, in his article Ueber den Begriff des Malerischen: "each new point of view must be combined with a new ideal of beauty (that is, a new concept)". Wölfflin "expresses a certain conception of the world which, going well beyond its formal dimension, contributes to the construction of its contents" (Panofsky).

Obsidian Fields is a new artistic phase of Vins Blake, in which the creative pulse and the way that the shots are taken create unusual images, that are remarkable and certainly different from what we have seen until now.

Marco Loi

Art Historian

Although photography is considered one of the forms of artistic communication, it is true that the creation process, after the idea, is a procedure that captures the truth of the real world as an image, whether on film or on a digital sensor. However, as photographic devices and techniques have evolved over time, so has our idea of reality, which has moved beyond that of a familiar cityscape or landscape.

The photographer, driven by a deep spirit of research, is no longer satisfied with man-made structures or what nature provides: he uses and manipulates what exists to capture new perspectives, novel variations on which to focus his lens, in an attempt to bring forth a different world. And it is exactly at this moment that this project is born, from Vins Blake, a photographer at the intersection of science and art, determined to tell a new story — that of the Obsidian Fields.

According to Ansel Adams, "You don't take a photograph, you make it.”, and this is what makes the difference in photography; the creative act is the moment when Blake combines the artist with his being a scientist, letting two worlds interact with each other and become reality, or, in this case, photography. The Obsidian Fields were still and unexplored realm, an idea set in motion at the interface between black pigment and glass, waiting to bloom according to the direction the mark left would take.

Chiaroscuro, shapes that occupy their space with soft but purposeful movements; an undefined microcosm that moves under the input of the photographer, on a surface that is circumscribed yet free at the same time. Reducing the lines to something known, familiar, takes away from the value of the images, which instead gain strength if we just follow that gentle movement of the color, expertly manipulated by the photographer, that becomes the generating principle of the entire series.

Static images that seem to move in space, traces that meet the gaze of the interlocutor who becomes a privileged observer, now able to look inside the narration itself, as if the circle were a window to lean out of, not the maximum limit within which to see. Photography as the beginning of the story, at the artist's will, while the rest of the discovery is the unique prerogative of the beholder.

Only by "reading" the entire Obsidian Fields series as if it were the pages of a book, will its meaning, value, and message be understood. Each shot a fragment of the story, each nuance a sentence, each trace a delicate thread to follow, in order to reach the creation’s inherent significance. Looking at the shots of Obsidian Fields means seeing through the eyes of the artist. No longer an investigative tool, they are organs capable of capturing a reality now made objective by the relationship between artistic intuition and that abstract space that has become the natural theater of the photographs.

The use of black acrylic — combined with the artistic idea — leaves the images suspended in their perspectival space, as in a continuous game in which Blake challenges himself by entrusting the observer with the nuances, the essence, without distorting the original message. Eminently fitting is a statement from Heinrich Wölfflin, art historian, in his article Ueber den Begriff des Malerischen: "each new point of view must be combined with a new ideal of beauty (that is, a new concept)". Wölfflin "expresses a certain conception of the world which, going well beyond its formal dimension, contributes to the construction of its contents" (Panofsky).

Obsidian Fields is a new artistic phase of Vins Blake, in which the creative pulse and the way that the shots are taken create unusual images, that are remarkable and certainly different from what we have seen until now.

Marco Loi

Art Historian

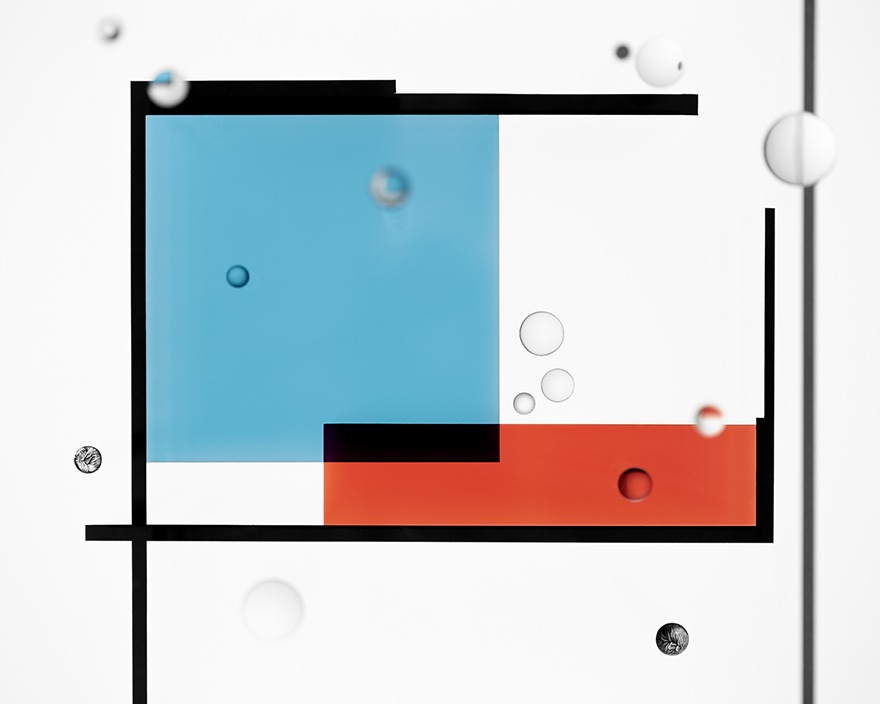

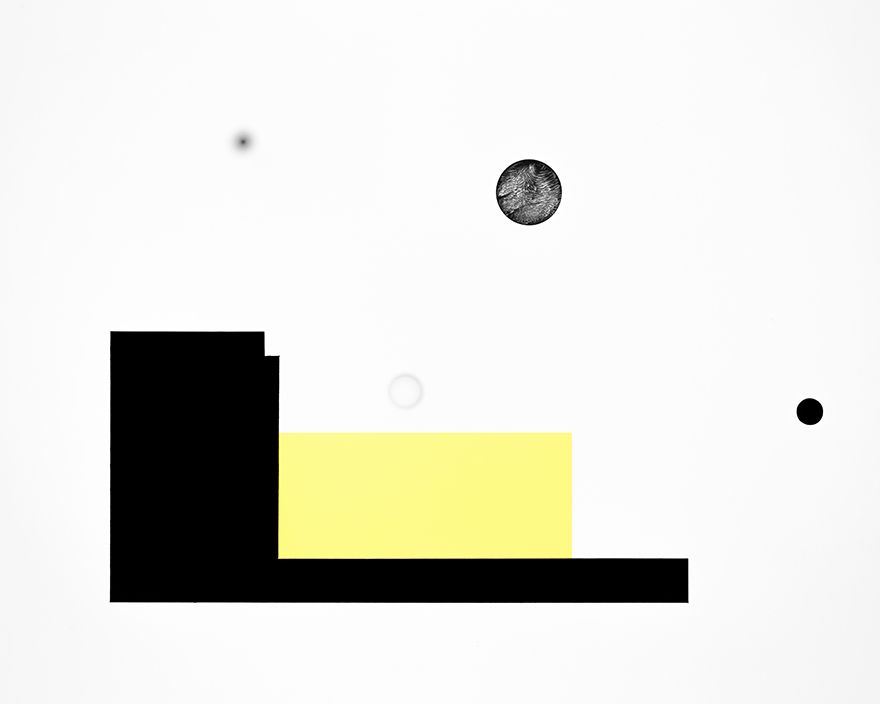

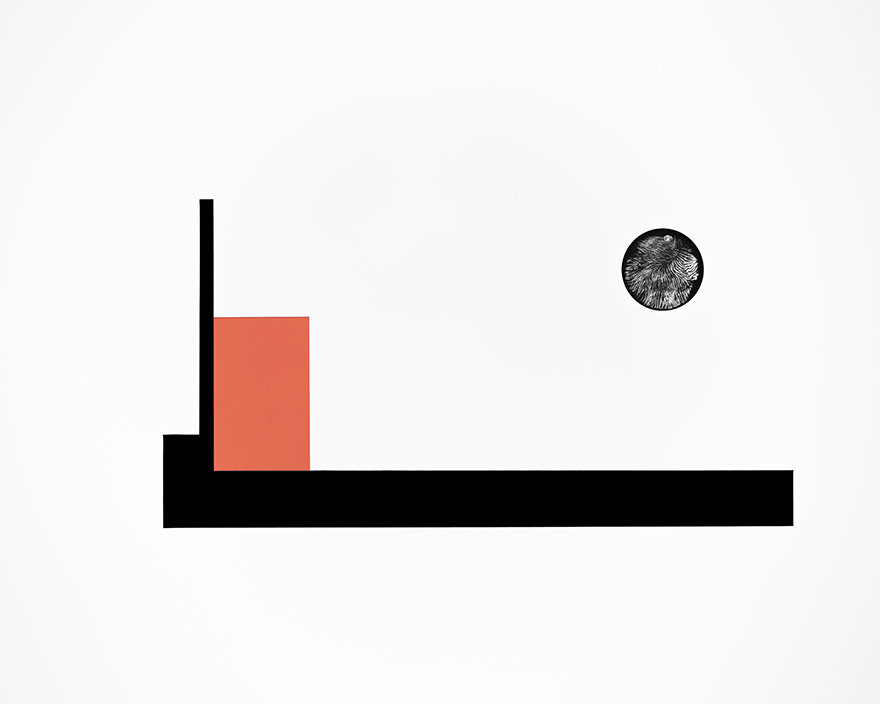

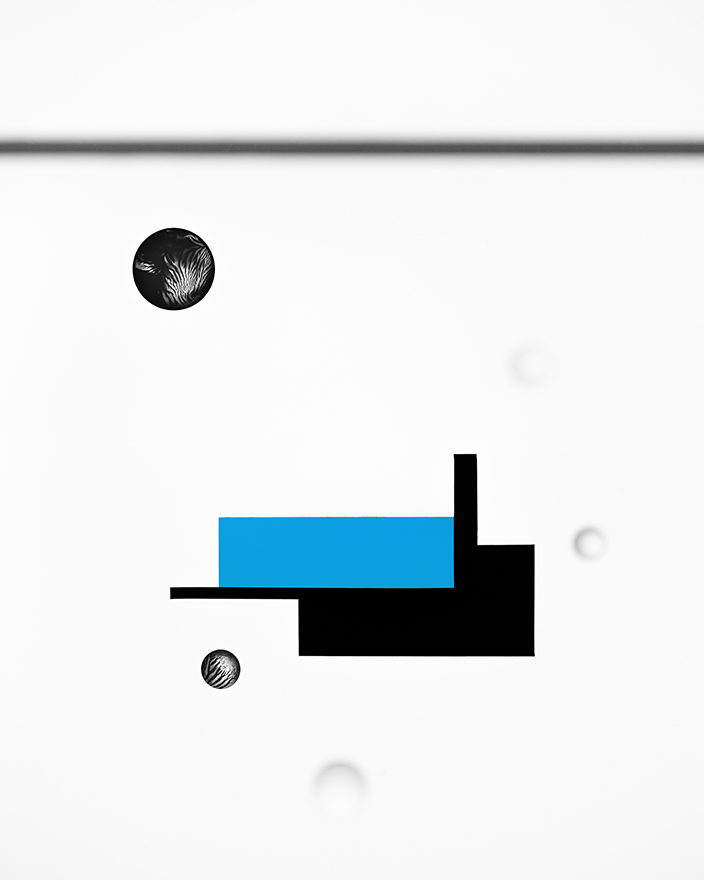

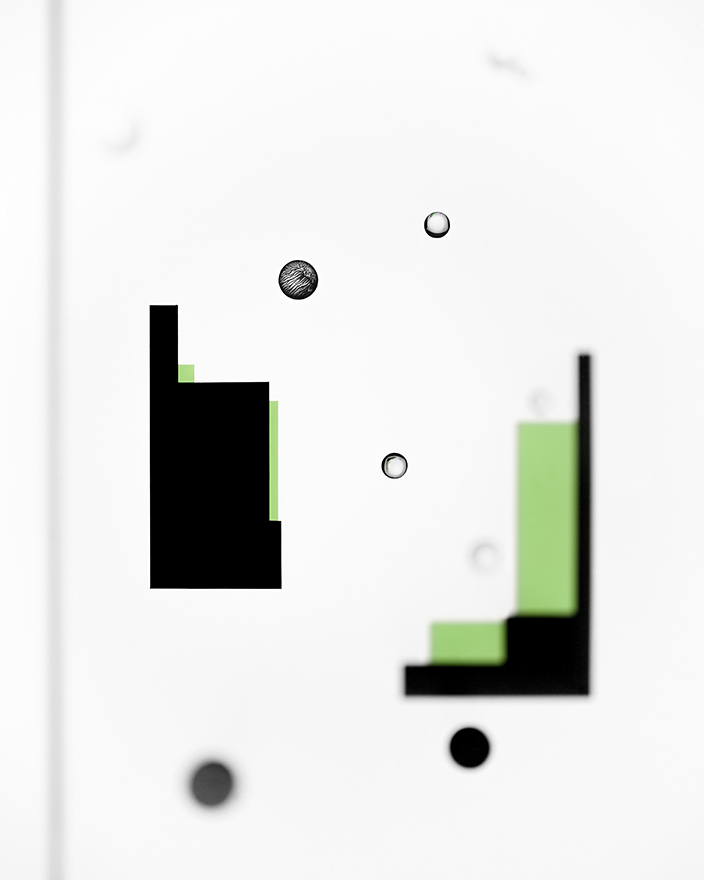

Soft and Restrained

Archival Pigment Print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag under Museum Glass (framed) | 2018 & 2019

Editions of 5 + 1AP: 86.5 x 74 cm (34 x 29 in)

Editions of 5 + 1AP: 86.5 x 74 cm (34 x 29 in)

|

|

|

||

Fading Universe |

Shelter |

Menace |

||

Editions of 5 + 1AP: 74 x 86.5 cm (29 x 34 in)

|

|

|||||

Erosion |

We Are Safe |

|||||

From the need to return to a state of calm, meditation, contemplation, in a milieu of constant aggressiveness that permeates and saturates tone and form, “Soft and Restrained” is born, a series of works driven by a minimalist reduction, yet holding true to its emotional substrate.

Our limens raise, victims of passive conditioning, while the constant noise that accompanies every moment becomes elemental, like a new, deceitful silence. Too many, unceasing stimuli lead to exhaustion and rejection, and the incessant request for vain attention invades every space and time.

Exploring the works of Mondrian (from 1919 onwards), and to a lesser extent those of Malevich (from 1915 to 1921) and Kandinsky (from 1922 to 1937), helps to slow down, to learn afresh to contemplate, and finally to lose oneself in a familiar geometry, albeit intriguing, teeming with passion and dynamism.

Protagonist, the line evolves and becomes an angle, creating a restrained neighbourhood that is rudimentary, yet intimate and personal. Intended as a refuge, it physically limits the permanent stream of instances and stimuli, partially obstructing their path.

Rarely the angle is symmetrical: as attention is delocalized, so the barrier is deformed, changing and adapting to circumstances. Rarely the angle is intact: as concentration can be eroded, so the barrier can lose its thickness.

Sculptures of ephemeral materiality, the compositions arise from parallel surfaces, both spatially and conceptually, before going back to their ultimate, bi-dimensional shape, like the works that have inspired them.

Vins Blake

Our limens raise, victims of passive conditioning, while the constant noise that accompanies every moment becomes elemental, like a new, deceitful silence. Too many, unceasing stimuli lead to exhaustion and rejection, and the incessant request for vain attention invades every space and time.

Exploring the works of Mondrian (from 1919 onwards), and to a lesser extent those of Malevich (from 1915 to 1921) and Kandinsky (from 1922 to 1937), helps to slow down, to learn afresh to contemplate, and finally to lose oneself in a familiar geometry, albeit intriguing, teeming with passion and dynamism.

Protagonist, the line evolves and becomes an angle, creating a restrained neighbourhood that is rudimentary, yet intimate and personal. Intended as a refuge, it physically limits the permanent stream of instances and stimuli, partially obstructing their path.

Rarely the angle is symmetrical: as attention is delocalized, so the barrier is deformed, changing and adapting to circumstances. Rarely the angle is intact: as concentration can be eroded, so the barrier can lose its thickness.

Sculptures of ephemeral materiality, the compositions arise from parallel surfaces, both spatially and conceptually, before going back to their ultimate, bi-dimensional shape, like the works that have inspired them.

Vins Blake

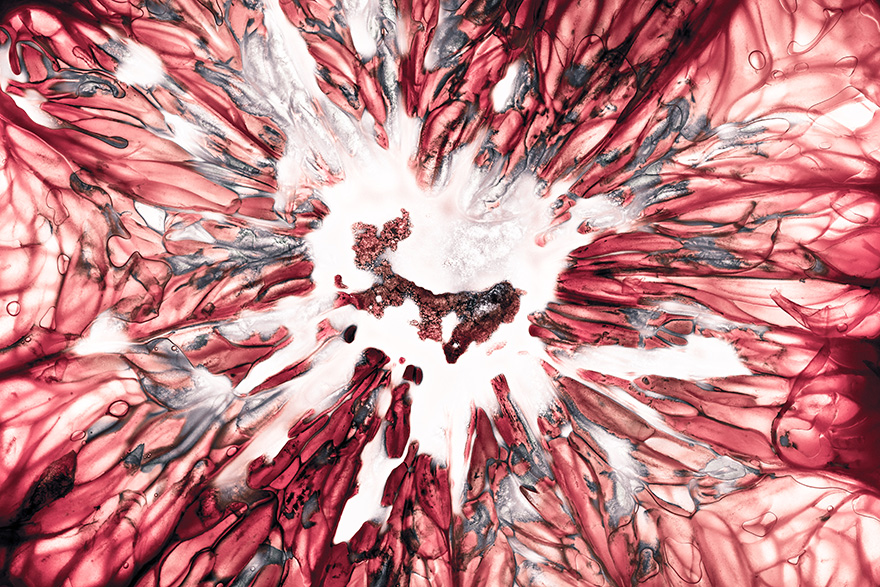

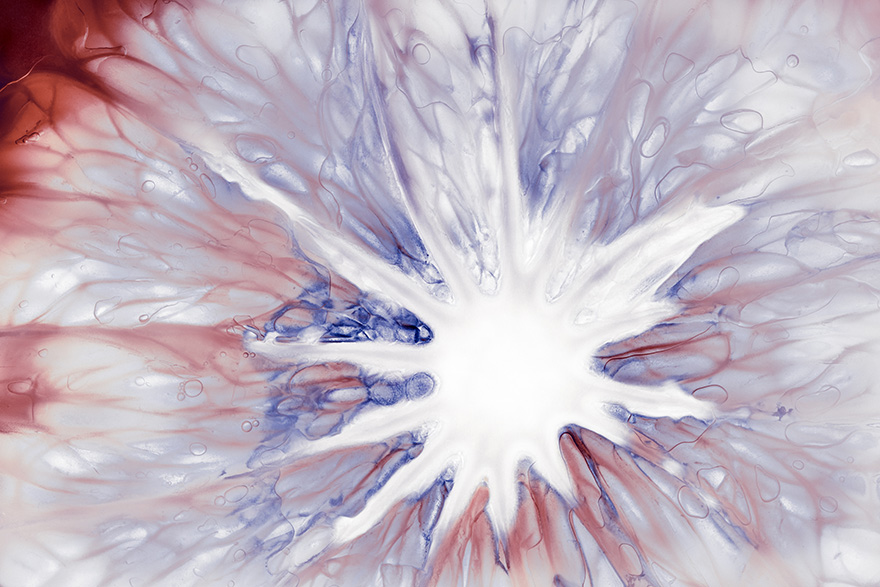

Anatomy of a Still Life

Fine Art Print on Aluminium (framed) | 2016 & 2017

Editions of 5 + 1AP: 98 x 68 cm (39 x 26 in)

Editions of 5 + 1AP: 98 x 68 cm (39 x 26 in)

|

|

|

||

Winking Boar |

Enlightenment |

Ice and Rust |

||

|

|

|

||

Grapefruit I |

Grapefruit II |

Grapefruit III |

||

Editions of 5 + 1AP: 110 x 128 cm (43 x 50 in)

|

||||

Grapefruit IV |

||||

“Of course, there will always be those who look only at technique, who ask ‘how’, while others of a more curious nature will ask ’why’”, said Man Ray. Approaching Vins Blake’s photography truly means embracing Ray’s words, leaving the “how” to the artist and

concentrating instead on the “why”, where unusual landscapes take form, in an experimental vision of modern photography that focusses on its origin, its Arche. Photography means writing with light, which, knowledgeably directed, becomes an instrument able to shape, infuse colour and substance, yet leaving the subject itself unchanged.

In Anatomy of a Still Life, Blake leaps even further in his investigation, transitioning from an exterior world, like the shells in Planets, to a veritable journey into nature itself; a narration by images supported by a scientist’s background, where his eye becomes a device able to guide our gaze beyond the surface.

Focussing on Enlightenment or Grapefruit I, we bridge the gap between the scientific approach, exclusively considered a prerogative of science, and photography, preserved in museums and art galleries. With Anatomy of a Still Life two systems are reunited, that were never separated if not by man, for science is the summa of those disciplines based essentially on observation, experience, and whose object in this instance are nature and its living beings.

If in Enlightenment we perceive the embryonic phase of Blake's new journey, also due to the very nature of the image, in the Grapefruit sub-series we seem to penetrate deep into the convolutions of the human mind, which makes its Journey to the Center of the Earth. “My imagination felt powerless before such immensity”, wrote Jules Verne in the famous novel and, without a doubt, it is what one feels in the presence of that universe, wanted by the artist to sublimate and exalt the heart of a fruit that now lets us catch a glimpse of the enormous, hidden wonder, simply called Nature.

Blake, as only great photographers can do, does not artificially construct a subject, but creates a visual narrative, capturing its primordial essence and, as only scientists can do, isolates an existing phenomenon by extrapolating it from its own world and finally bringing it closer to our senses. For this reason, every shot becomes both a paraphrase and a synthesis of its subject, between the real and the intellectual spheres, a window from which to investigate another way of interpreting modern photography.

Marco Loi

Art Historian

In Anatomy of a Still Life, Blake leaps even further in his investigation, transitioning from an exterior world, like the shells in Planets, to a veritable journey into nature itself; a narration by images supported by a scientist’s background, where his eye becomes a device able to guide our gaze beyond the surface.

Focussing on Enlightenment or Grapefruit I, we bridge the gap between the scientific approach, exclusively considered a prerogative of science, and photography, preserved in museums and art galleries. With Anatomy of a Still Life two systems are reunited, that were never separated if not by man, for science is the summa of those disciplines based essentially on observation, experience, and whose object in this instance are nature and its living beings.

If in Enlightenment we perceive the embryonic phase of Blake's new journey, also due to the very nature of the image, in the Grapefruit sub-series we seem to penetrate deep into the convolutions of the human mind, which makes its Journey to the Center of the Earth. “My imagination felt powerless before such immensity”, wrote Jules Verne in the famous novel and, without a doubt, it is what one feels in the presence of that universe, wanted by the artist to sublimate and exalt the heart of a fruit that now lets us catch a glimpse of the enormous, hidden wonder, simply called Nature.

Blake, as only great photographers can do, does not artificially construct a subject, but creates a visual narrative, capturing its primordial essence and, as only scientists can do, isolates an existing phenomenon by extrapolating it from its own world and finally bringing it closer to our senses. For this reason, every shot becomes both a paraphrase and a synthesis of its subject, between the real and the intellectual spheres, a window from which to investigate another way of interpreting modern photography.

Marco Loi

Art Historian

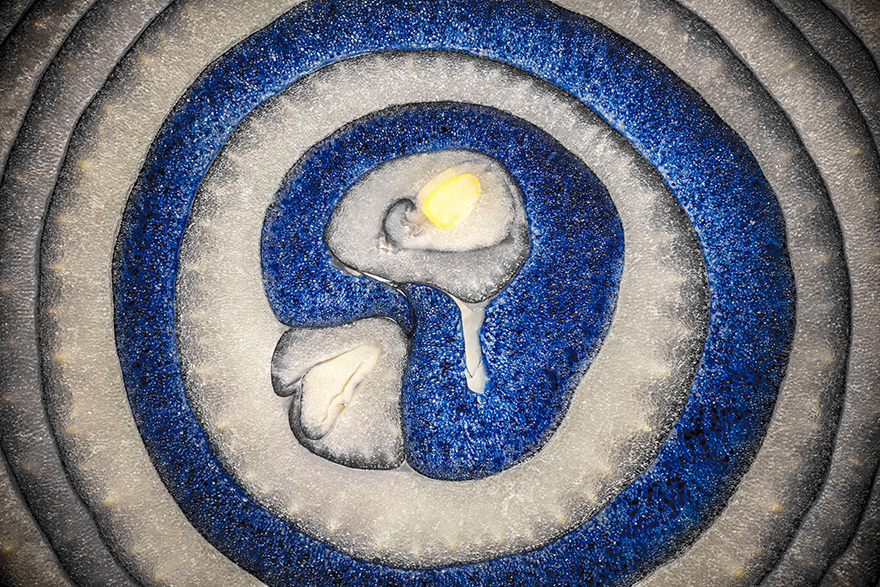

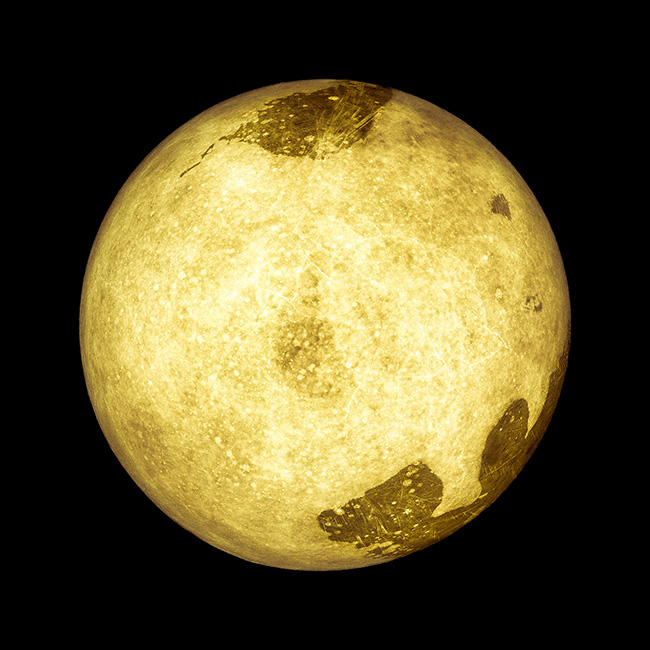

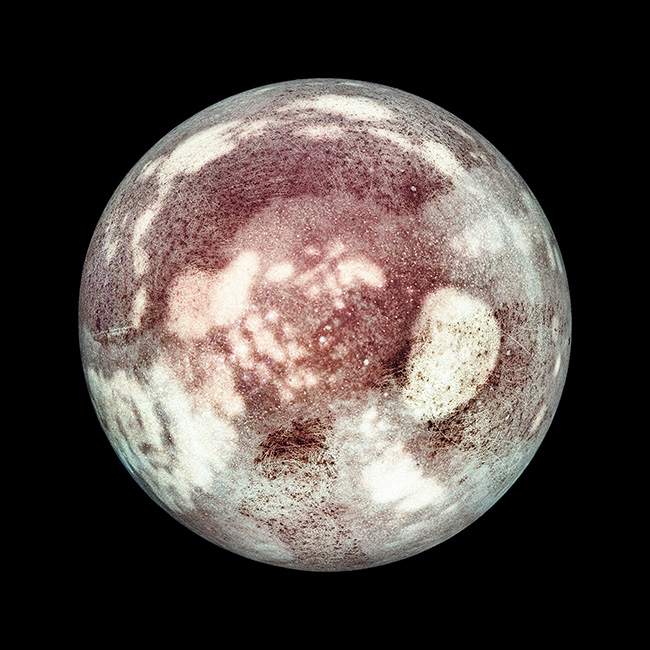

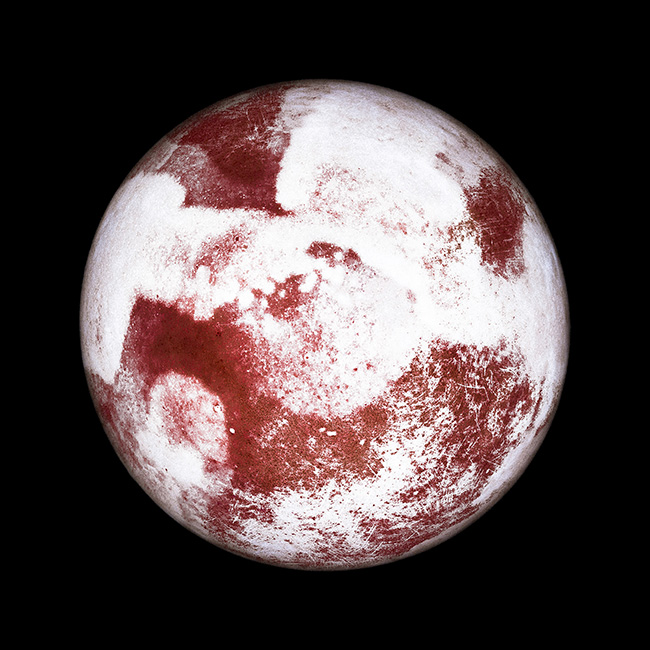

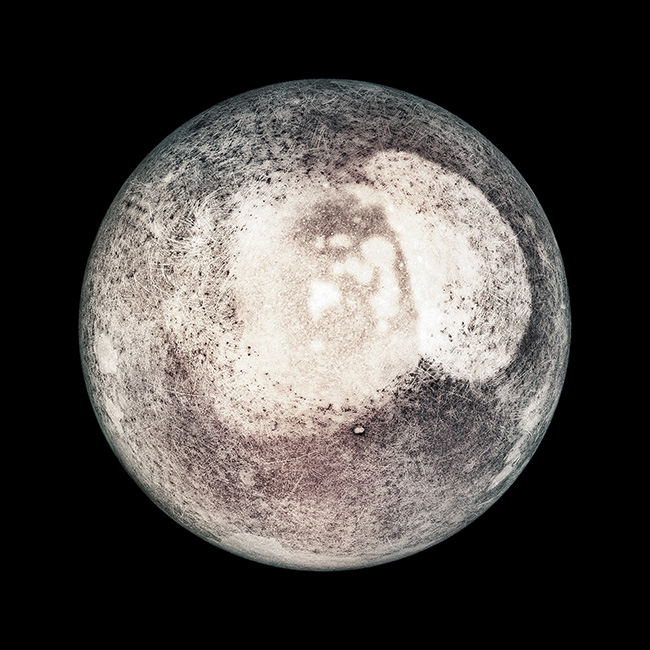

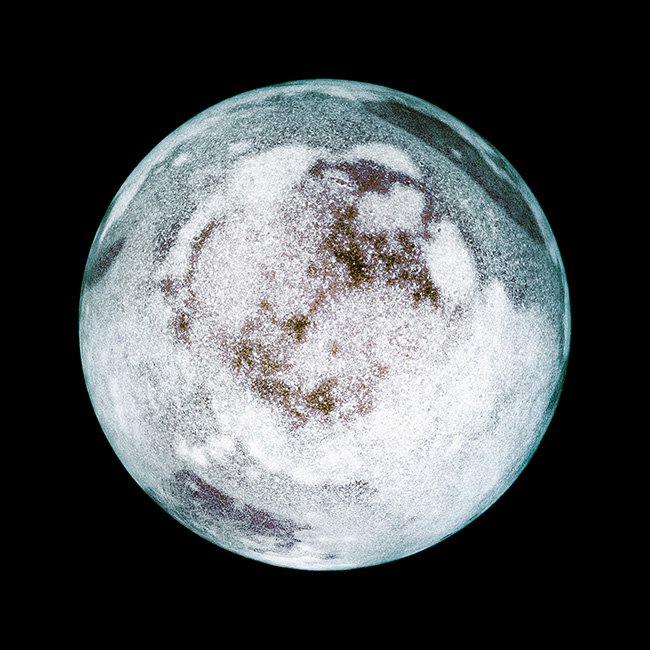

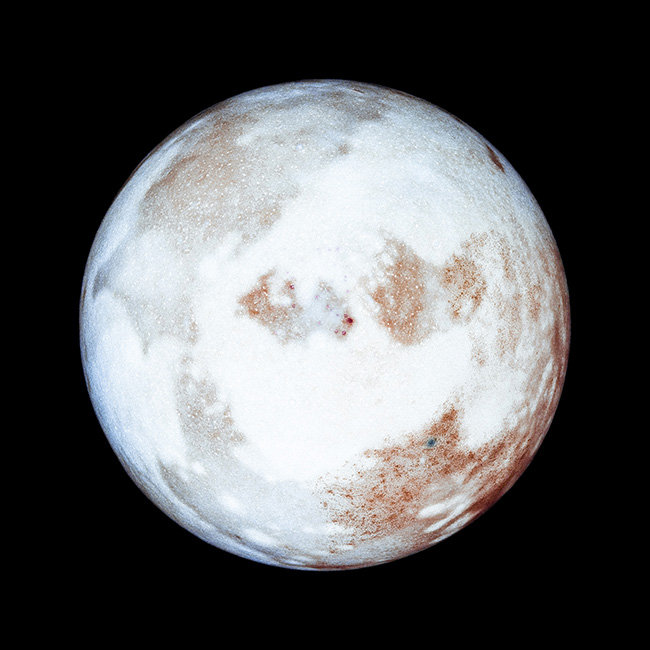

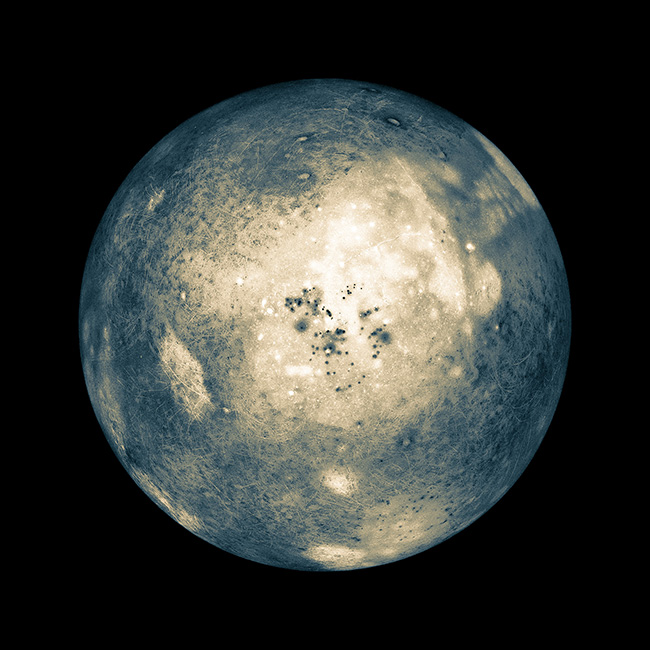

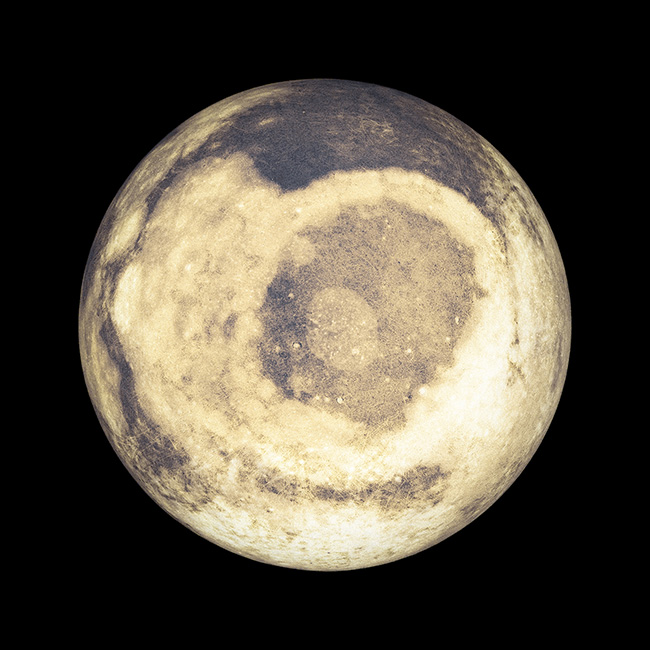

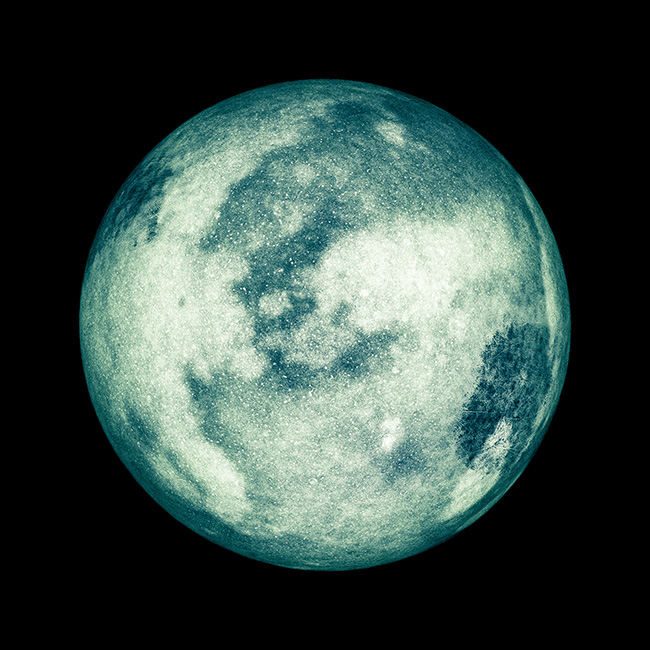

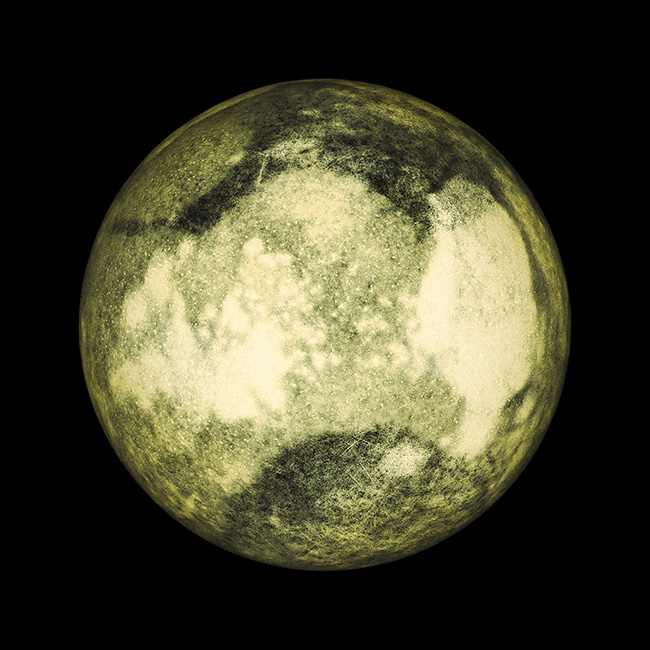

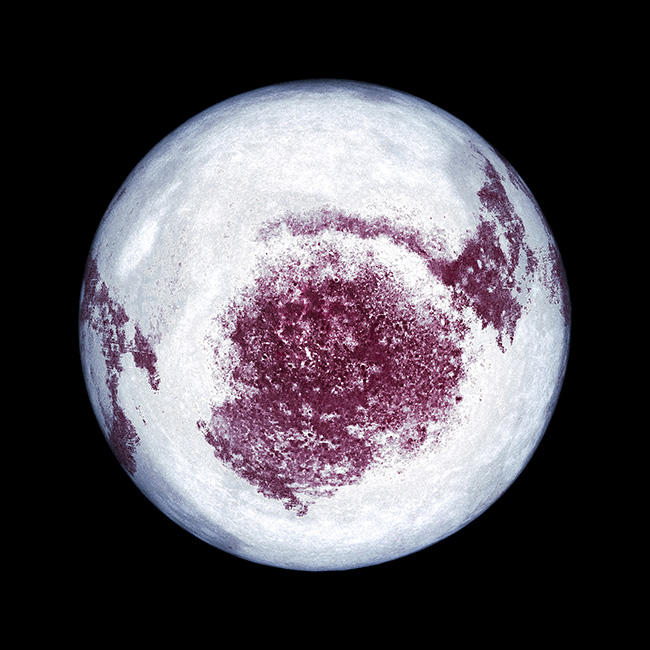

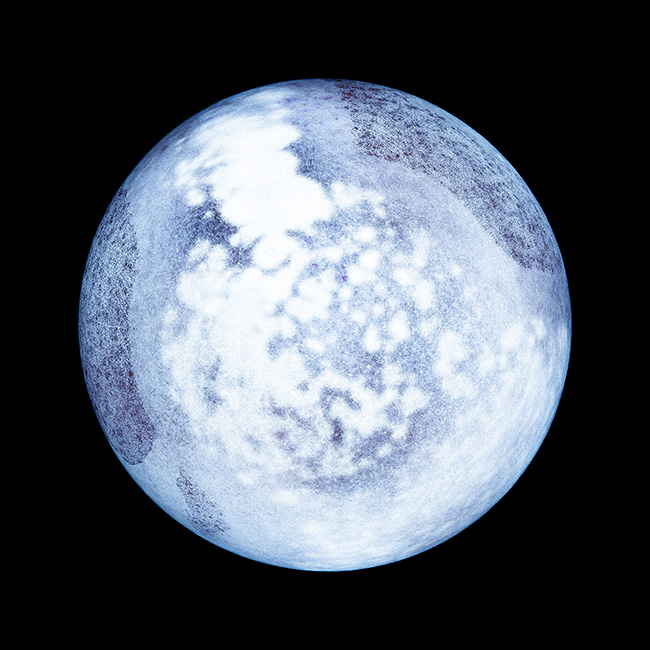

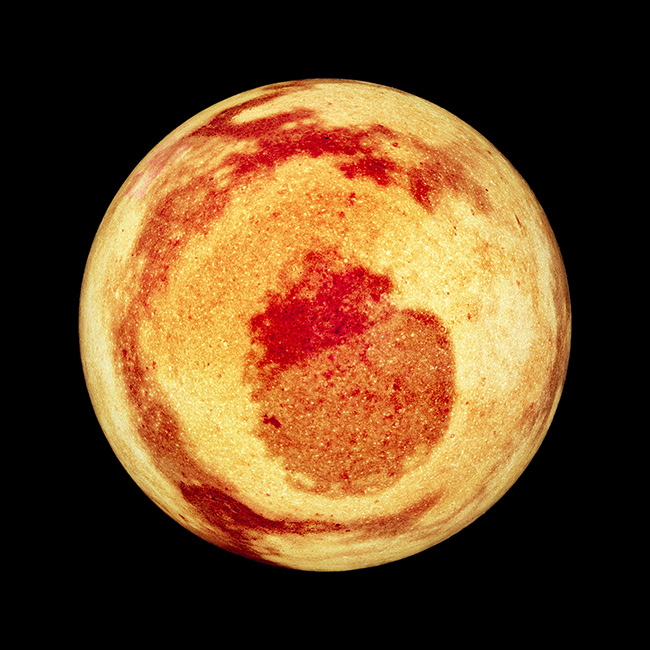

Planets

Lambda C-type Prints under Acrylic Glass | 2016

Editions of 9 + 1AP: 100 x 100 cm (39 x 39 in)

Editions of 5 + 1AP: 140 x 140 cm (55 x 55 in)

Editions of 9 + 1AP: 100 x 100 cm (39 x 39 in)

Editions of 5 + 1AP: 140 x 140 cm (55 x 55 in)

|

|

|

|

|||

Gamma 1 |

Gamma 2 |

Gamma 3 |

Gamma 5 |

|||

|

|

|

|

|||

Gamma 6 |

Gamma 7 |

Gamma 8 |

Gamma 9 |

|||

|

|

|

|

|||

Gamma 10 |

Gamma 11 |

Gamma 12 |

Gamma 13 |

|||

|

|

|

||||||

Gamma 14 |

Gamma 15 |

Gamma 16 |

||||||

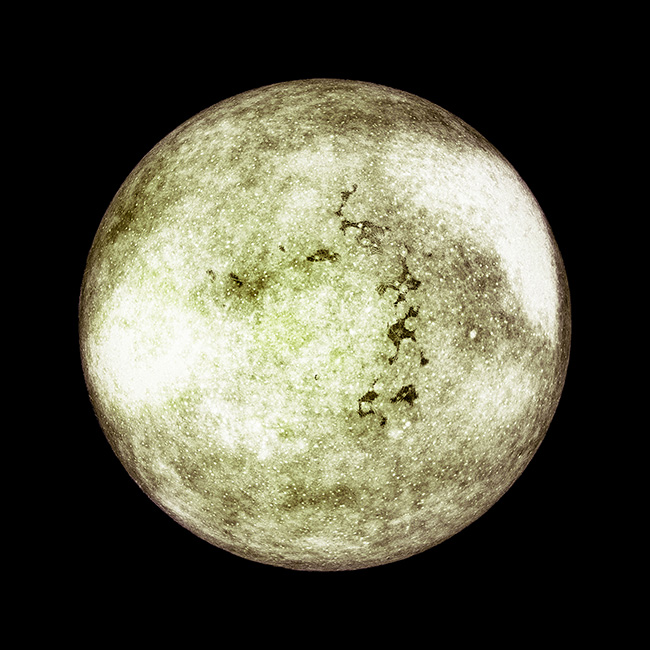

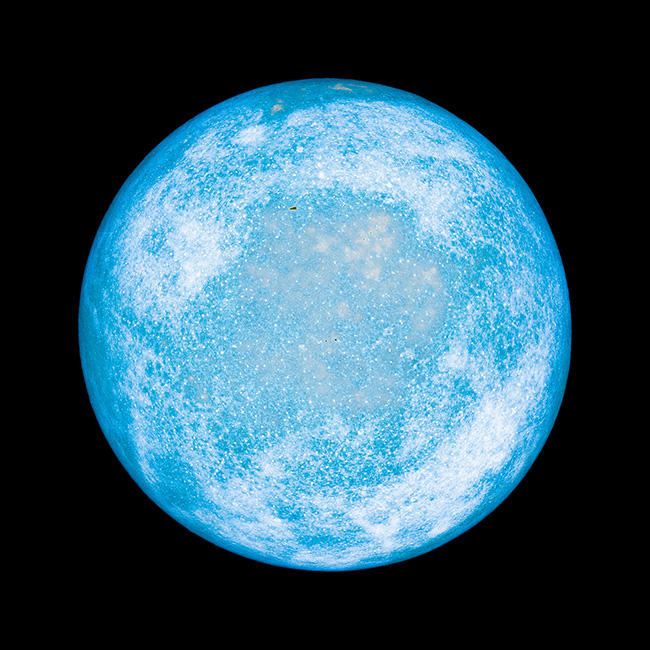

Vins Blake is an Italian Photographer and Film Director with a rather unconventional background. A scientist by training – he holds an MSc in Biotechnology – Vins felt early on in his career a strong fascination with art, which eventually led him to develop a vision of the world filtered through the prism of his scientific studies. While “art washes away from the soul the dust of everyday life” – as Pablo Picasso once said – through the masterful application of chemistry and electronic engineering Vins Blake challenges our perception of reality by subtly playing with everyday objects.

The Planets series was precisely born from this process. What at a casual glance can look like a celestial body viewed from a satellite is in fact nothing more than a common egg, chemically manipulated and shot in the comfort of the artist’s studio.

Decontextualising objects is nowadays a widely accepted artistic practice, however Vins Blake’s originality is in the fresh approach to art through science, blending the two and bridging the gap between scientific rigour and artistic creativity. Blake’s choice to use the perfect shape of an egg to recreate images of planets is bewildering and fascinating at the same time. These “planets” seem to truly float in outer space, thanks to the dark background that isolates the subjects and highlights their intrinsic features. This illusion is then enhanced by the medium used to print the photos, Lambda C-type prints under acrylic glass, which makes the planets appear bright, vivid and in effect real.

Looking at Blake’s use of light and colour one cannot but think of the work of a champion of science photography, Berenice Abbott. Although she strongly advocated the use of unaltered subjects and un-manipulated photographs, Blake’s works can nonetheless be understood in the wake of Abbott’s project to photograph scientific phenomena. While Abbott’s aim was to facilitate science interpretation by didactically describing the physical world, Blake’s goal is to create, through science, aesthetically captivating images to capture the attention of the casual viewer and at the same time demonstrate that the beauty of nature can be appreciated even from such an unconventional standpoint.

Marco Loi

Art Historian

The Planets series was precisely born from this process. What at a casual glance can look like a celestial body viewed from a satellite is in fact nothing more than a common egg, chemically manipulated and shot in the comfort of the artist’s studio.

Decontextualising objects is nowadays a widely accepted artistic practice, however Vins Blake’s originality is in the fresh approach to art through science, blending the two and bridging the gap between scientific rigour and artistic creativity. Blake’s choice to use the perfect shape of an egg to recreate images of planets is bewildering and fascinating at the same time. These “planets” seem to truly float in outer space, thanks to the dark background that isolates the subjects and highlights their intrinsic features. This illusion is then enhanced by the medium used to print the photos, Lambda C-type prints under acrylic glass, which makes the planets appear bright, vivid and in effect real.

Looking at Blake’s use of light and colour one cannot but think of the work of a champion of science photography, Berenice Abbott. Although she strongly advocated the use of unaltered subjects and un-manipulated photographs, Blake’s works can nonetheless be understood in the wake of Abbott’s project to photograph scientific phenomena. While Abbott’s aim was to facilitate science interpretation by didactically describing the physical world, Blake’s goal is to create, through science, aesthetically captivating images to capture the attention of the casual viewer and at the same time demonstrate that the beauty of nature can be appreciated even from such an unconventional standpoint.

Marco Loi

Art Historian